“MEMORY OF THE CITY_ Milosh Luczynski in JUBILATKA” _ 19.07_30.08 2024, Krakow, Nowa Huta, Poland.

curator MALGORZATA SZYDLOWSKA

2 months long multidisciplinary intervention: art exposition, participatory, monumental video installation, intermedia shows .

The former restaurant JUBILATKA, located at Teatralne Estate 11, experienced its heyday alongside the flourishing of the steelworks complex. Over time, however, it began to decline. Eventually, a place that was once bustling with social life turned into a “deserted” space. Thanks to the artist intervention, we are breathing new life into this place that was once important to many residents of Nowa Huta / Krakow.

For six summer weeks (from July 19 to August 30), JUBILATKA will transform into a meeting place for the residents of Nowa Huta. The artist will take over the space of the former restaurant and turn it into a studio-gallery, where you will be able to meet him for most of these days.

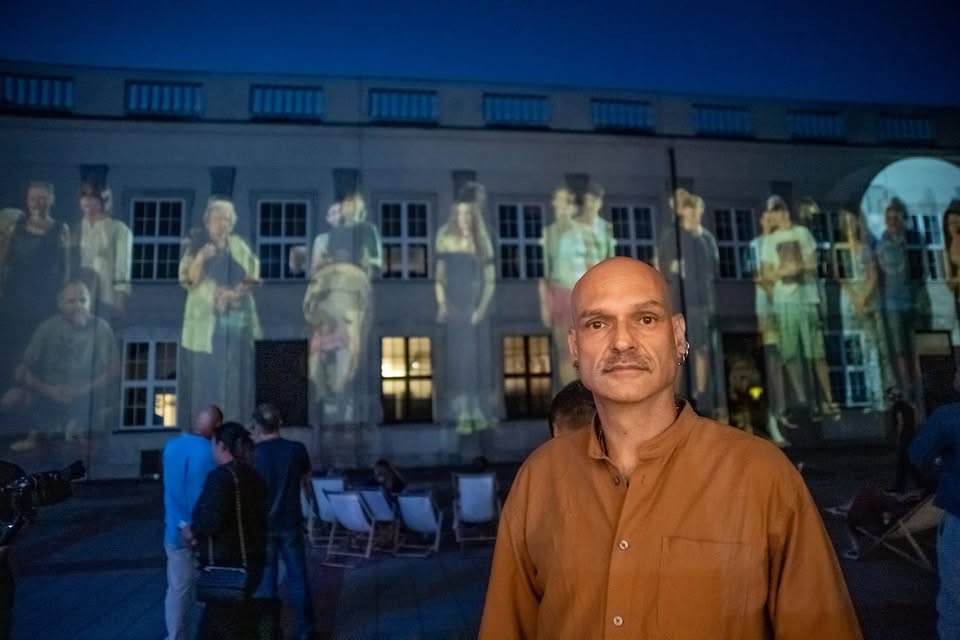

The results of the artist’s work will be visible on Friday evenings on the walls of the former KINO ŚWIT, in the form of large-format multimedia projections, where we will see the faces of Nowa Huta residents who shared their stories with us, including those about the social life of Nowa Huta.

MILOSH LUCZYNSKI will bring to Nowa Huta works from his latest exhibition titled “I see the boundless arrogance of my prejudices, I am only human” to engage in a dialogue with the recently discovered works of Nowa Huta artist Marian Kruczek (1927-1983), known, among other things, for the “Pod chmurką” gallery and many other activities that culturally enlivened Nowa Huta in the 1970s. Both artists share not only a particular empathy towards nature but also kinship. Their artistic “meeting” will turn into a familial artistic epic.

💫 In the Jubilatka space, you will also be able to see unknown works of the Kruczek artistic family connected to Nowa Huta: Józefa Sobór-Kruczek (1930-2001), Paweł Kruczek (1952-2022), and Katarzyna Szadkowska (born 1985).

Review by Katarzyna Bednarczyk and link to the interview Strzępy miasta below.

“Recovery”

On the side facade of the old Świt Cinema, a row of several-meter-high figures emerges in the light. The concrete square between the cinema and the building of the long-gone Jubilatka restaurant fills with a stream of voices. A theatrical spotlight begins to move, summoning one figure after another to share their stories. It chooses without judgment—here, there are no better or worse stories, no linear progression or cause-and-effect. There are fragments of stories about Nowa Huta, associations, flashes of what is not (fully) conscious but presses to be spoken, heard, and remembered—not just by the speaker, but also by the listeners. The personal memory of the city’s individual inhabitants transcends their personal boundaries, becoming a shared, collective memory, giving it a chance to endure.

But before this happens, a good place is needed—a space where people meet and trust one another enough to share their stories with strangers, with others. ML thus occupies rooms in a place that long ago was a restaurant and, more recently, a bookstore, toy shop, and stationery store. In both functions, it was perhaps not iconic but maybe better because it was ordinary, familiar, and close by. Now, stripped of these functions, it stands empty and impersonal. ML says that he is beginning a peaceful, legal occupation of this space, though the word “occupation” with its warlike connotations doesn’t resonate with the kind of space he’s creating here. There is no aggression or brutality here. The largest room is filled with works by him and his family of Nowa Huta artists, connected by blood ties. Here, where people once ate, drank, danced, sold, bought, and did countless other things too many to name, objects resembling sacred relics appear—not from some distant time or place, but from here, and only just beginning to exist. This might intimidate potential visitors, but it doesn’t. Maybe it’s the light, warm like a campfire, that invites them in. The darker it gets outside, the more it draws them in.

When someone, lured by the light, steps inside, a conversation begins. Many stories are told just beyond the threshold, never repeated or recorded in the nearby studio. People come with different motivations. An elderly man arrives, having had a conflict with his wife that escalated to physical violence. His hands are bandaged, and he seeks calm. A middle-aged woman comes in, as she says, drunk, but her curiosity is not dulled—she wants to know what’s happening here and chat about it for a while. A young man comes, having just lost his mother the night before. He wants to record something for her, as if ML and his recordings could be a bridge between here and there, between him and her. An elderly woman arrives because it’s hot outside, and here, both she and her dog, who enjoys lying on the cool tiles, can escape the heat. A teenage boy, always in a baseball cap, comes in. He’s quiet and doesn’t explain why he’s there, but he shows up repeatedly, and in the last few days, he begins to smile. Here, you can imagine the rest of the story for yourself. Many people come, drawn by curiosity and the desire to be, for a moment, somewhere else—in some different reality, which they find here.

Out of a much larger group of visitors, one hundred people decide to stand in front of the green screen of the improvised studio and record their stories. It’s hard to summarize what they talk about in a few words—something is always lost, flattened. The gestures, the tone of voice, those moments of hesitation and sudden inspiration when memory suddenly brings up something that must be shared—those moments when emotions overflow and run their course cannot be captured. There’s laughter, singing, trembling voices, and moist eyes. Stories about going sledding, getting ice cream, seeing a movie, taking a walk, first jobs, last jobs, falling in love, neighbors, greenery, concrete, family, tribal fights, help, rooting and re-rooting, returns, gains, and losses. Another list that doesn’t list everything, because the stories are as varied as the people who came with them. Expectations can’t be trusted here; you can’t let your mind fill in the gaps and offer a ready-made image of the speaker too quickly. Like when a very elderly man, over ninety years old, begins to speak. He talks about events from the year ‘23, and the listener automatically fills in 1923, ignoring the fact that he would be the oldest person alive on Earth if that were the case. His story is about love, about a woman, Marysia, whom he met during a walk, befriended, and soon lost when she unexpectedly passed away. He speaks about his farewell to her, the most terrible event of his life, which happened not decades ago but just a few months earlier. His story defies expectations of someone his age—he’s not the archetypal old man or sage who will tell us about the beginnings of Nowa Huta, sprinkled with wisdom about the passage of time. Instead, he gives us something fresh, something painfully present. If stories can be tools for generating empathy and opening up to the realities of others, then this one is surely such a tool.

This story, along with dozens of others, contributes to the record of what is remembered about Nowa Huta in the summer of 2024. Arranged in an order not decided by ML but by fate—a roll of the dice—they form a structure where chronology doesn’t exist, and time runs in circles rather than straight lines. It loops back as stories return to where they happened. The place from the past meets the place from today, reflected in it over and over. Geographically, everything is almost as it was—Nowa Huta is still here, but beyond geography? Newness in Nowa Huta, changes, maturation, crumbling, evolution, shifts. When night falls, the installation is no longer projected inside the cinema like movies once were but onto its side wall, in relation to the architecture rather than as on a screen. Anyone, intentionally or by chance, who arrives in the square between Świt, Jubilatka, the three linden trees, and the concrete steps can see and hear it. Light brings forth a row of towering figures, and the air fills with a stream of voices. What Memory of the City the viewer draws from it depends on the viewer.

Katarzyna Bednarczyk

Odzyskiwanie.

Na bocznej fasadzie dawnego Kina Świt światło wyłania rząd kilkumetrowych figur. Betonowy plac między kinem, a budynkiem nieistniejącej restauracji Jubilatka wypełnia strumień głosów. Teatralny reflektor zaczyna się poruszać i wywołuje kolejne postaci, aby opowiedziały to, z czym przyszły. Wybiera bez wartościowania, tu nie ma lepszych i gorszych opowieści, nie ma też liniowości czy następstwa przyczyna – skutek. Są fragmenty historii o Nowej Hucie, skojarzenia, przebłyski tego co nie (w pełni) uświadomione, ale ciśnie się na usta i chce być wypowiedziane, usłyszane i zapamiętane, już nie tylko przez mówiące(go), ale i słuchaczy. Indywidualna pamięć miasta jednostki przekracza jej ramy, staje się pamięcią wspólną, dzieloną, a to daje jej szanse na przetrwanie.

Zanim jednak do tego dojdzie, potrzebne jest dobre miejsce, gdzie człowiek spotyka człowieka i ufa na tyle, by temu drugiemu, obcemu i innemu, a potem drugim, obcym i innym opowiadać. ML zajmuje więc pomieszczenia w miejscu, które dawno temu było restauracją, a do niedawna sklepem z książkami, zabawkami i artykułami papierniczymi. W obu funkcjach raczej nie kultowym, ale może lepszym, bo zwykłym, swojskim i obecnym tuż obok. Teraz tych funkcji pozbawionym, pustym i nieludzkim. Mówi, że rozpoczyna pokojową, legalną okupację tej przestrzeni, choć słowo “okupacja” ze swoimi wojennymi konotacjami nie rezonuje z przestrzenią, którą tu stwarza. Ta nie ma w sobie agresji, ani brutalności. Powierzchnię największej sali zapełnia pracami swoimi oraz rodziny nowohuckich artystów, z którą łączą go więzy krwi. Tu, gdzie kiedyś jedzono, pito, tańczono, sprzedawano, kupowano i robiono mnóstwo innych rzeczy, które długo by nazywać, pojawiają przedmioty przypominające obiekty kultu, ale nie odległego w czasie i przestrzeni, a tutejszego i dopiero możliwego do zaistnienia. To mogłoby onieśmielać potencjalnych gości, ale tak się nie dzieje. Może za sprawą światła, ciepłego jak z ogniska, które zachęca do wejścia. Im ciemniej na zewnątrz, tym przyciąga bardziej.

Kiedy zwabiony nim człowiek wejdzie do środka, rozpoczyna się rozmowa. Wiele opowieści pada zaraz za progiem, nie są potem powtarzane i nagrywane w studiu obok. Przynoszących je ludzi do wejścia popychają różne motywacje. Przychodzi starszy mężczyzna, któremu konflikt z żoną wyeskalował do przemocy fizycznej, ma zabandażowane ręce, chce się uspokoić. Przychodzi kobieta w średnim wieku, jak sama mówi, pijana, ale alkohol nie stłumił jej ciekawości, chce wiedzieć, co tu się dzieje i chwilę o tym porozmawiać. Przychodzi młody mężczyzna, któremu poprzedniej nocy zmarła matka, chce nagrać coś dla niej, jakby ML i jego nagrania mogły być mostem między tu i tam, nim a nią. Przychodzi starsza kobieta, bo na zewnątrz jest upał, a tu mogą się przed nim schować i ona i jej pies, który lubi poleżeć na zimnych płytkach. Przychodzi nastoletni chłopak, zawsze w czapeczce z daszkiem, cichy, nie mówi, co go sprowadza, ale pojawia się wielokrotnie, w ostatnie dni zaczyna się uśmiechać i tu opowieść można/trzeba dopowiedzieć sobie samemu. Przychodzi… mnóstwo ludzi, których łączy ciekawość i chęć bycia przez moment gdzieś indziej, w jakiejś odmiennej rzeczywistości, tu ją znajdują.

Sto osób z o wiele liczniejszej grupy przychodzących decyduje się stanąć na zielonym tle zaimprowizowanego studia i nagrać swoje historie. O czym mówią, trudno dobrze streścić w kilku słowach, coś tu zawsze umyka, spłaszcza się, brak gestu, brzmienia głosu, tych zawahań i olśnień, kiedy pamięć podrzuca nagle to coś, co trzeba opowiedzieć; momentów, kiedy emocje nie dają się stłumić i płyną jak chcą. Jest śmiech, śpiew, drżący głos i wilgotne oczy. Są historie o wyjściu na sanki, lody, film, spacer, pierwszej pracy, ostatniej pracy, zakochaniu, sąsiadach, zieleni, betonie, rodzinie, plemiennych bójkach, pomocy, zakorzenieniu i zakorzenianiu, powrotach, zysku i utracie… Kolejna wyliczanka, co nie wylicza wszystkiego, bo opowieści są różne, jak ludzie, którzy z nimi przyszli. Nie można się tu dać zwieść oczekiwaniom, pozwolić by mózg wypełnił luki i zbyt szybko podrzucił gotową wizję mówiącego. Jak wtedy, kiedy głos zabiera mocno starszy, ponad dziewięćdziesięcioletni mężczyzna. Mówi o wydarzeniach z roku 23. i słuchacz od razu dopowiada sobie 1923, ignorując fakt, że byłby to wtedy najstarszy żyjący człowiek na Ziemi. Jego opowieść jest o miłości, o kobiecie, o Marysi, którą poznał podczas spaceru, z którą się zaprzyjaźnił i którą stracił niebawem, kiedy niespodziewanie zmarła. Opowiada o pożegnaniu z nią, co było najstraszniejszym wydarzeniem jego życia i stało się nie dekady, a kilka miesięcy wcześniej. Przeczy wyobrażeniom o osobie w swoim wieku, o tym archetypicznym starcu, czy mędrcu, który powie jak wyglądały prapoczątki Nowej Huty i okrasi to mądrością na temat czasu, co od wtedy upłynął. Zamiast tego daje nam coś świeżego, bolesne (niemal) teraz. Jeśli opowieści mogą być narzędziami do wzbudzania empatii i otwierania się na rzeczywistość innych, to ta jest takim narzędziem na pewno.

Ona i kilkadziesiąt innych historii składają się na zapis tego, co pamiętane o Nowej Hucie latem 2024 roku. Ustawione w kolejności, o której zdecydował nie ML, a los – rzut kostką, tworzą strukturę, gdzie chronologia nie zachodzi, a czas biegnie raczej po okręgach, niż w linii prostej. Zatacza kolejne pętle, kiedy opowieści wracają, gdzie się wydarzyły. Miejsce z kiedyś spotyka miejsce z dziś i przegląda się w nim po wielokroć. Geograficznie wszystko jest niemal tak, jak było, Nowa Huta jest wciąż tutaj, a poza geografią? Nowe w Nowej, zmiany, dojrzewanie, kruszenie, ewolucja, przesunięcia. Kiedy zapada zmrok instalacja wyświetlana jest już nie we wnętrzu kina, jak kiedyś filmy, a na jego bocznej ścianie i nie jak na ekranie, a w relacji z architekturą. Zobaczyć i usłyszeć może ją każdy, kto celowo bądź przypadkiem zjawi się na placu między Świtem, a Jubilatką, trzema lipami, a schodami z betonu. Światło wyłania tu rząd kilkumetrowych figur, powietrze wypełnia strumień głosów, jaką Pamięć Miasta widz z niego wyłowi, zależy już od widza.

Katarzyna Bednarczyk

photos: Artur Rakowski, Katarzyna Bednarczyk

Subsidised by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland from the Fund for the Promotion of Culture – a state purpose fund.